MUSEO THYSSEN - BORNEMISZA

MUSEO THYSSEN BORNEMISZA

OTTO DIX

TÉCNICAS Y SECRETOS - RETRATO DE HUGO ERFURT

TECHNIQUES AND SECRETS - PORTRAIT OF HUGO ERFURT

OTTO DIX

Y Hugo Erfurth

And Hugo Erfurth

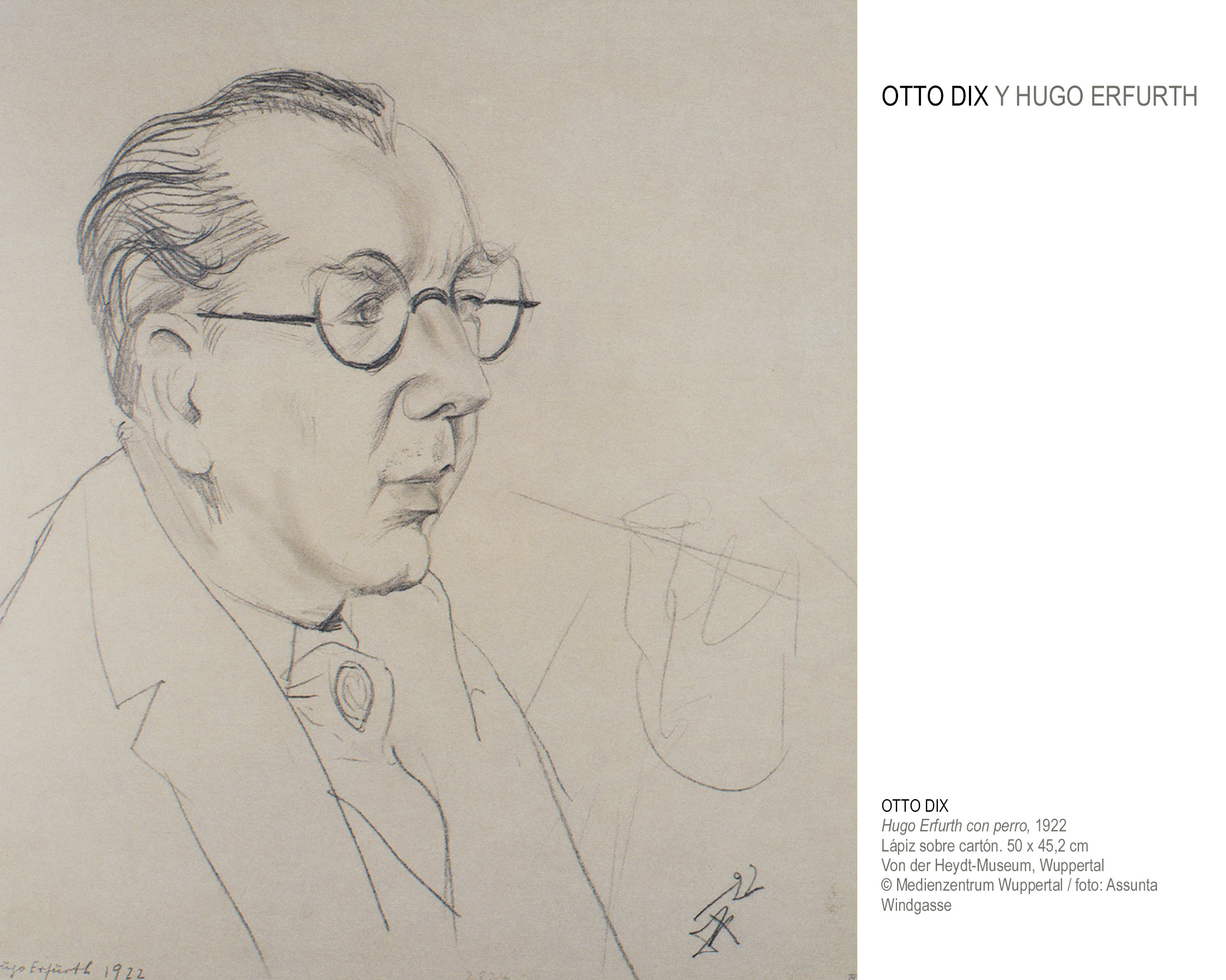

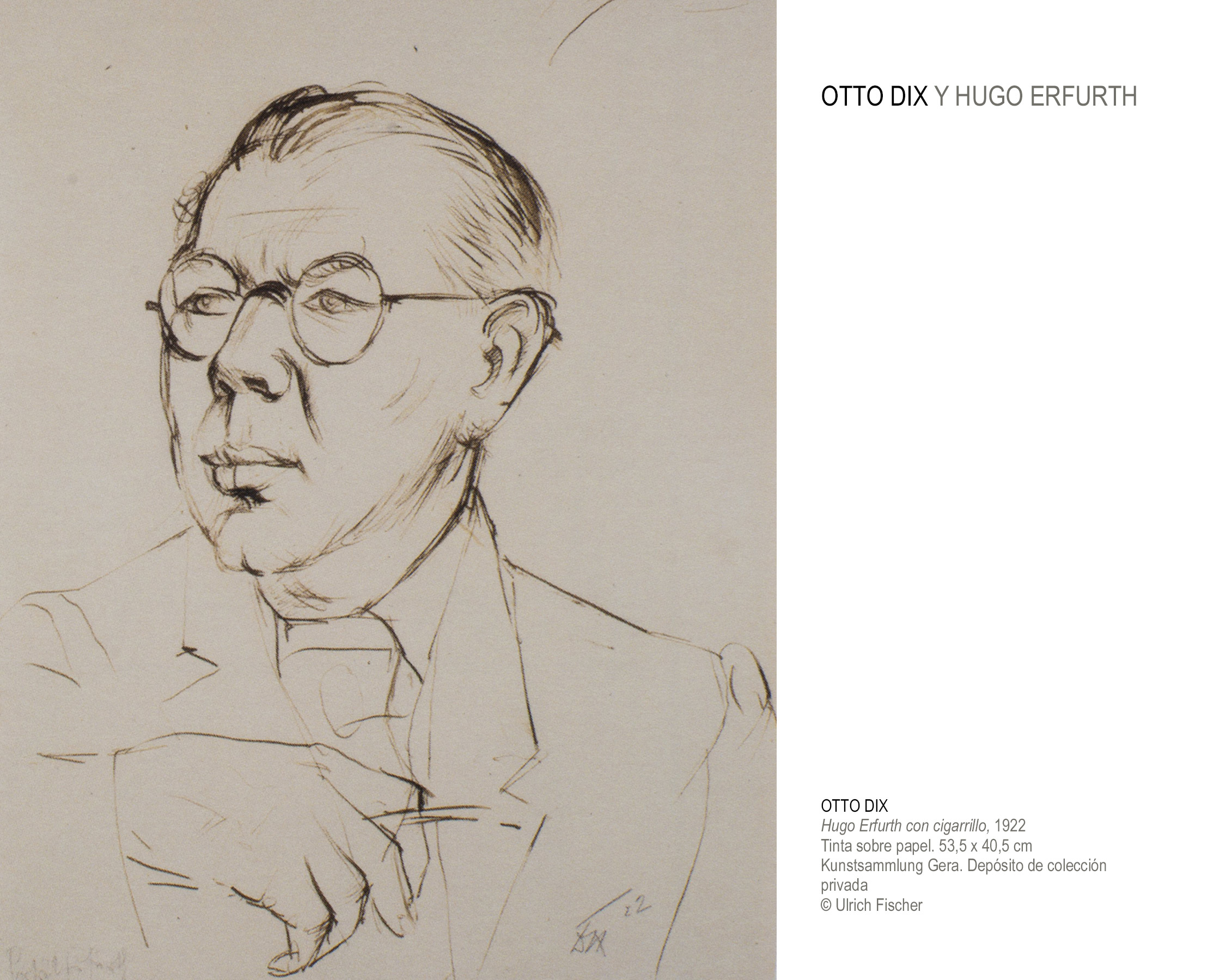

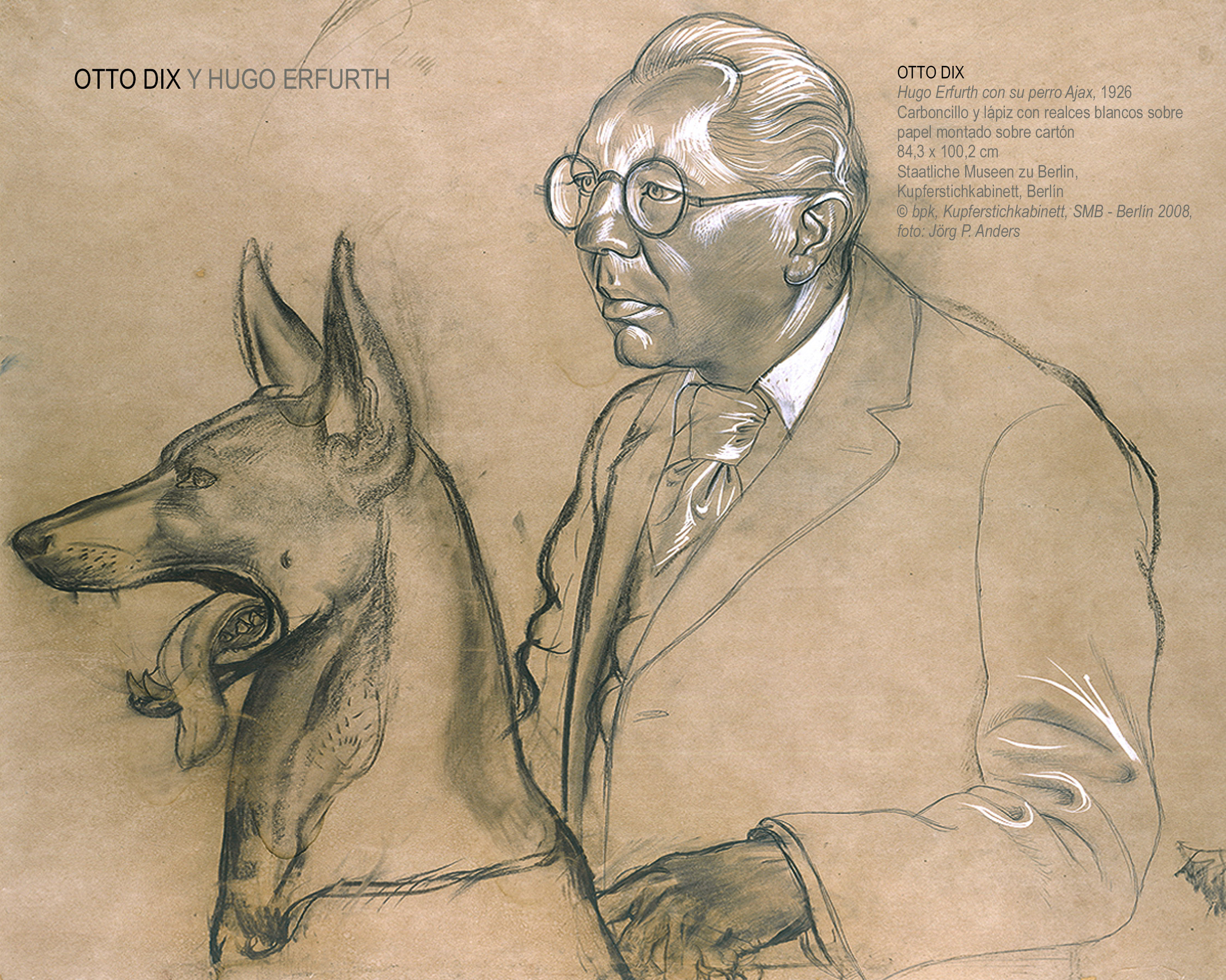

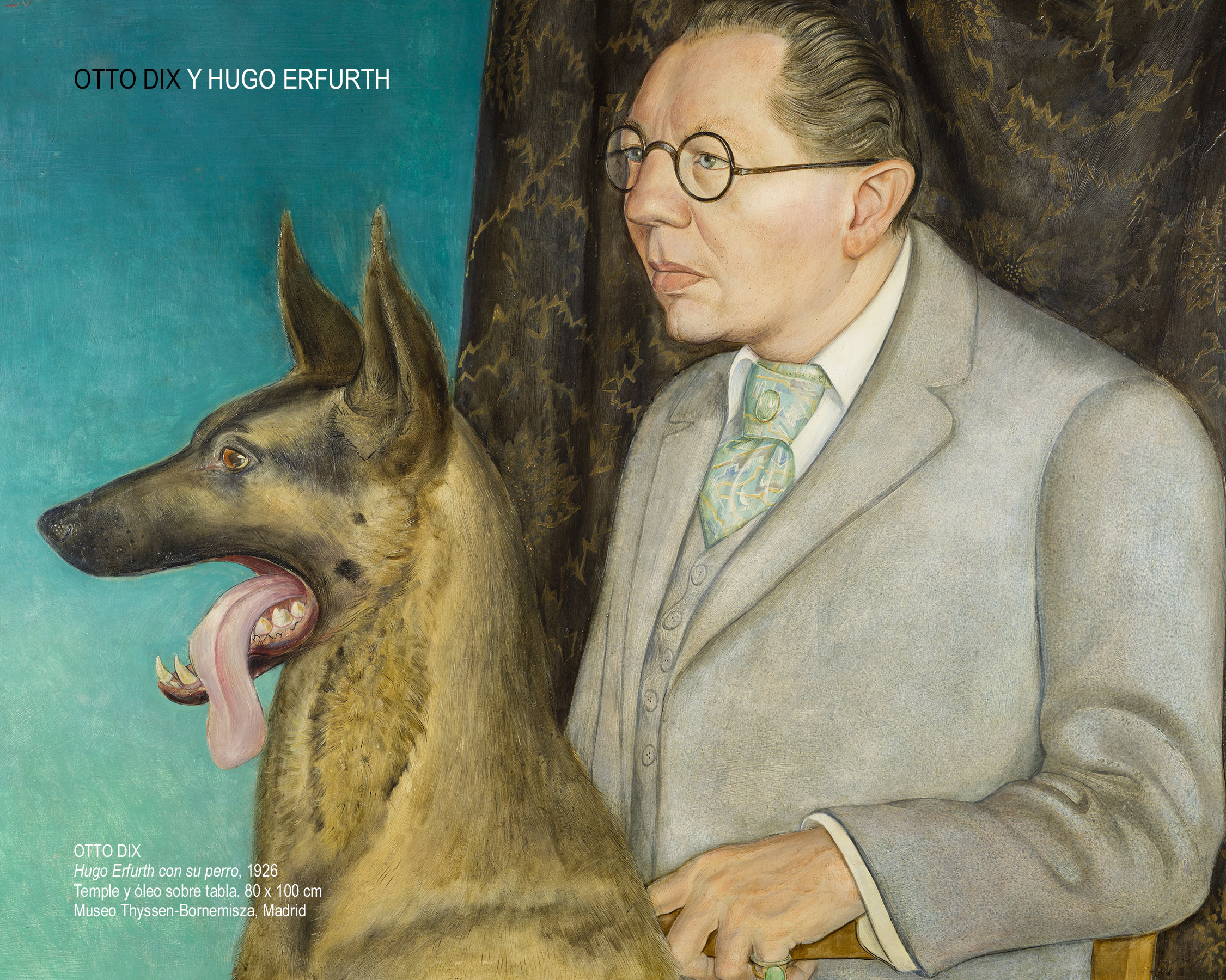

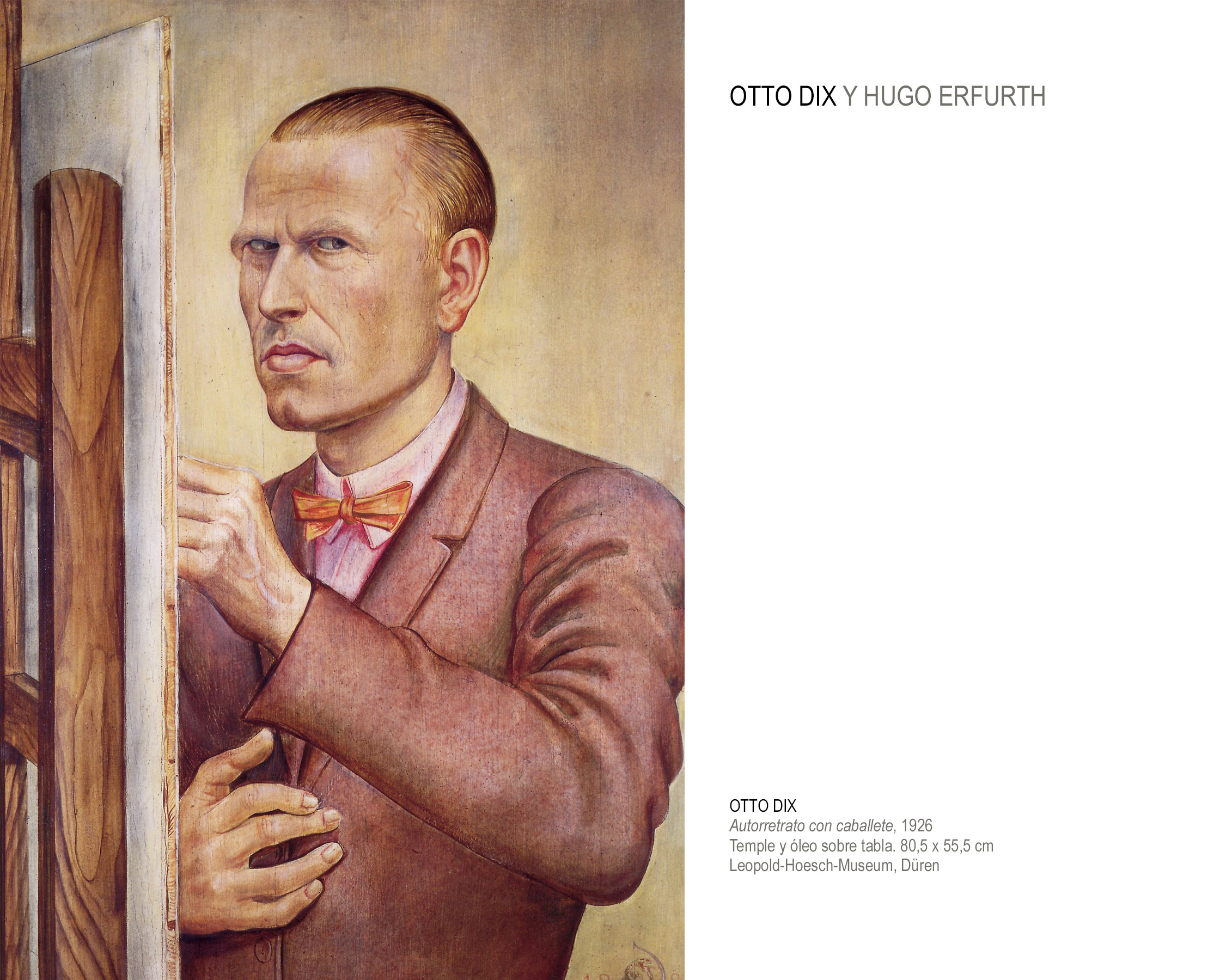

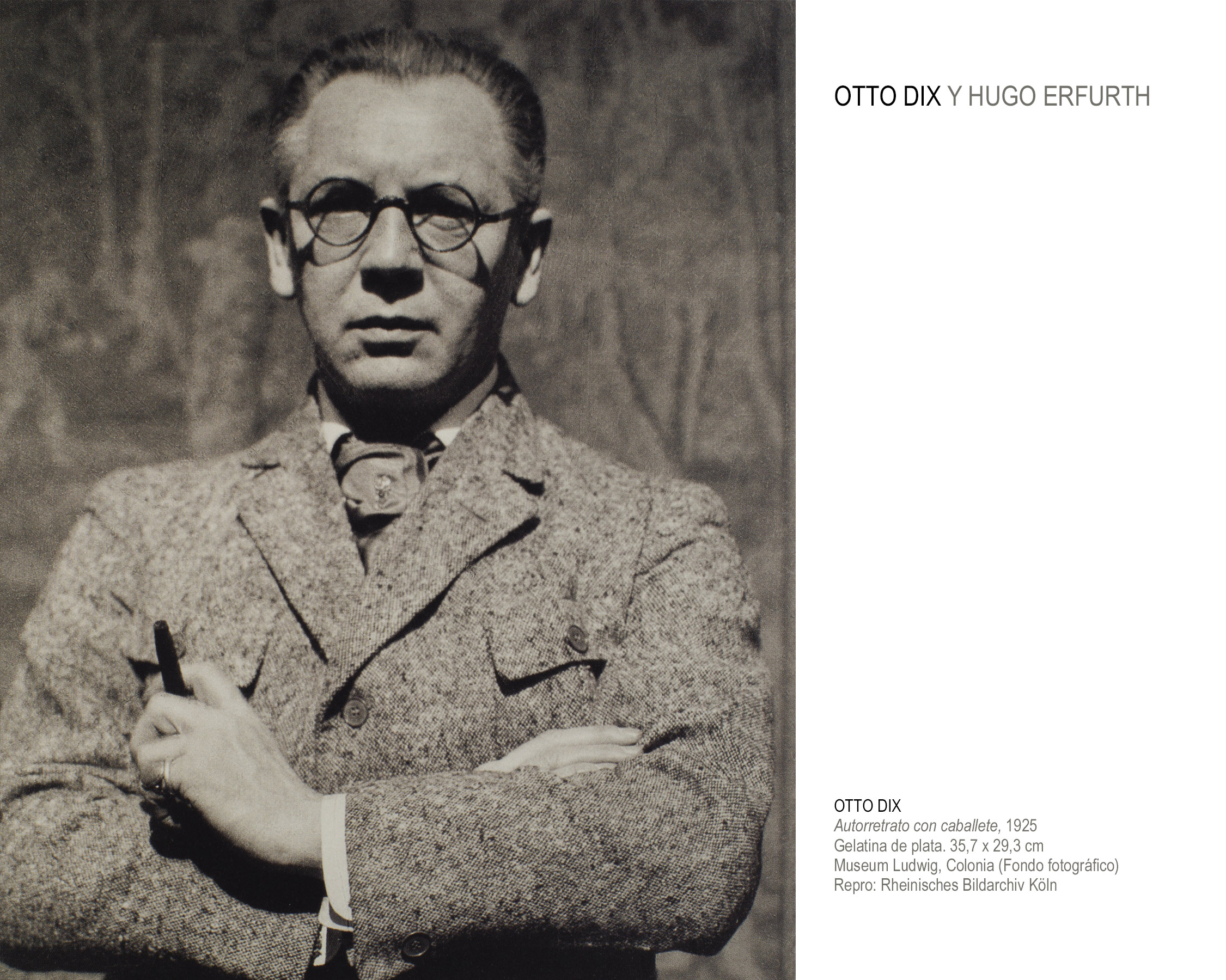

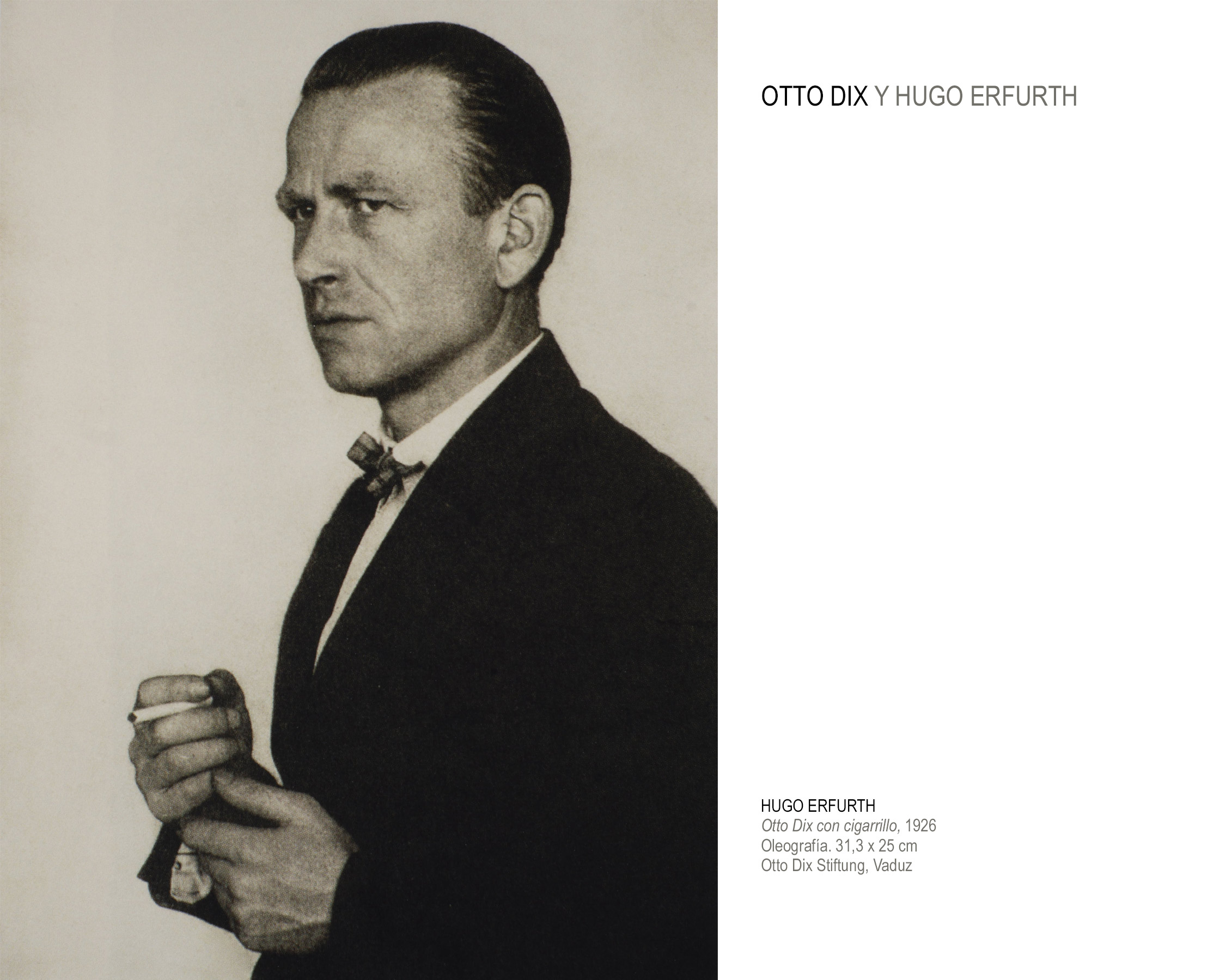

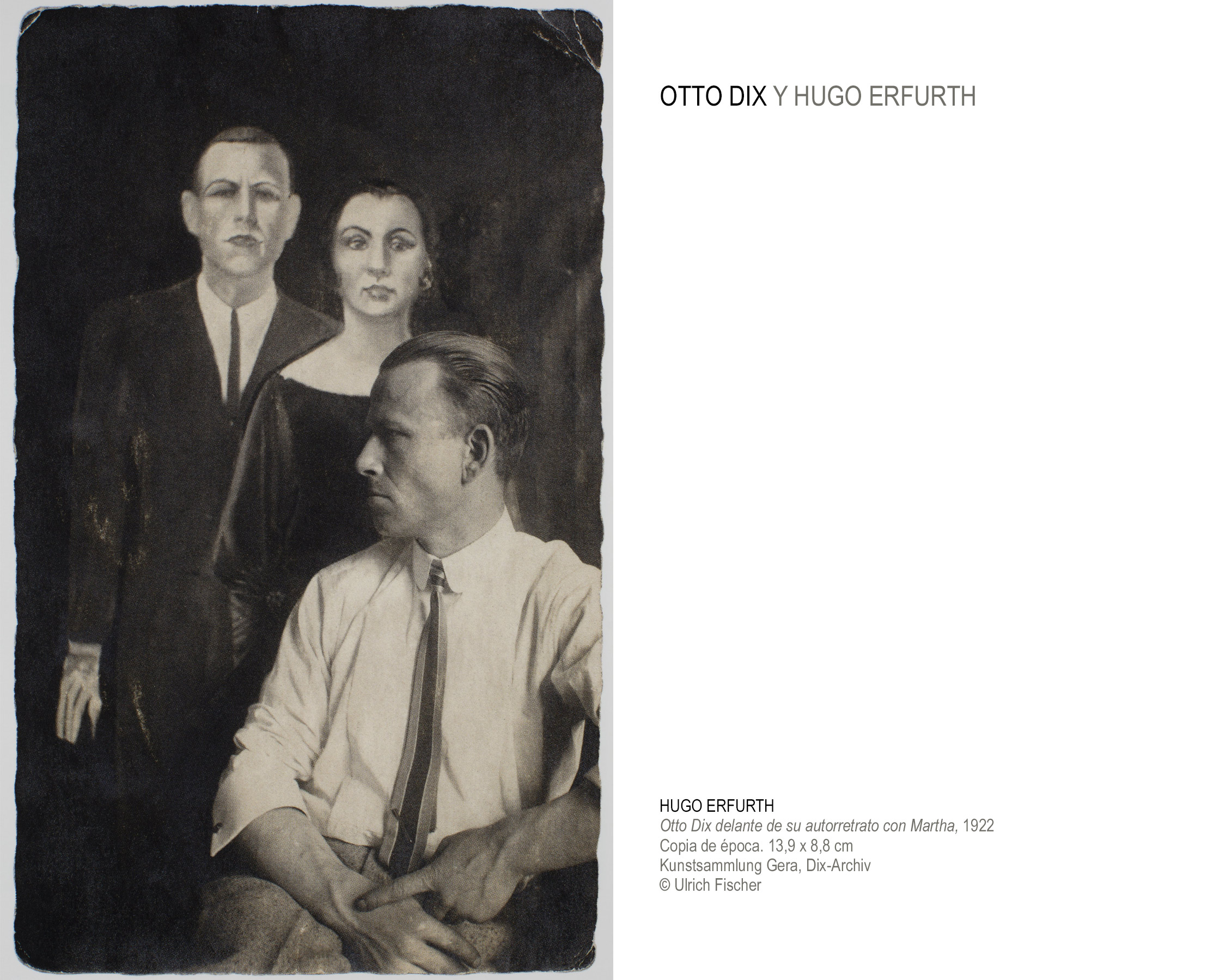

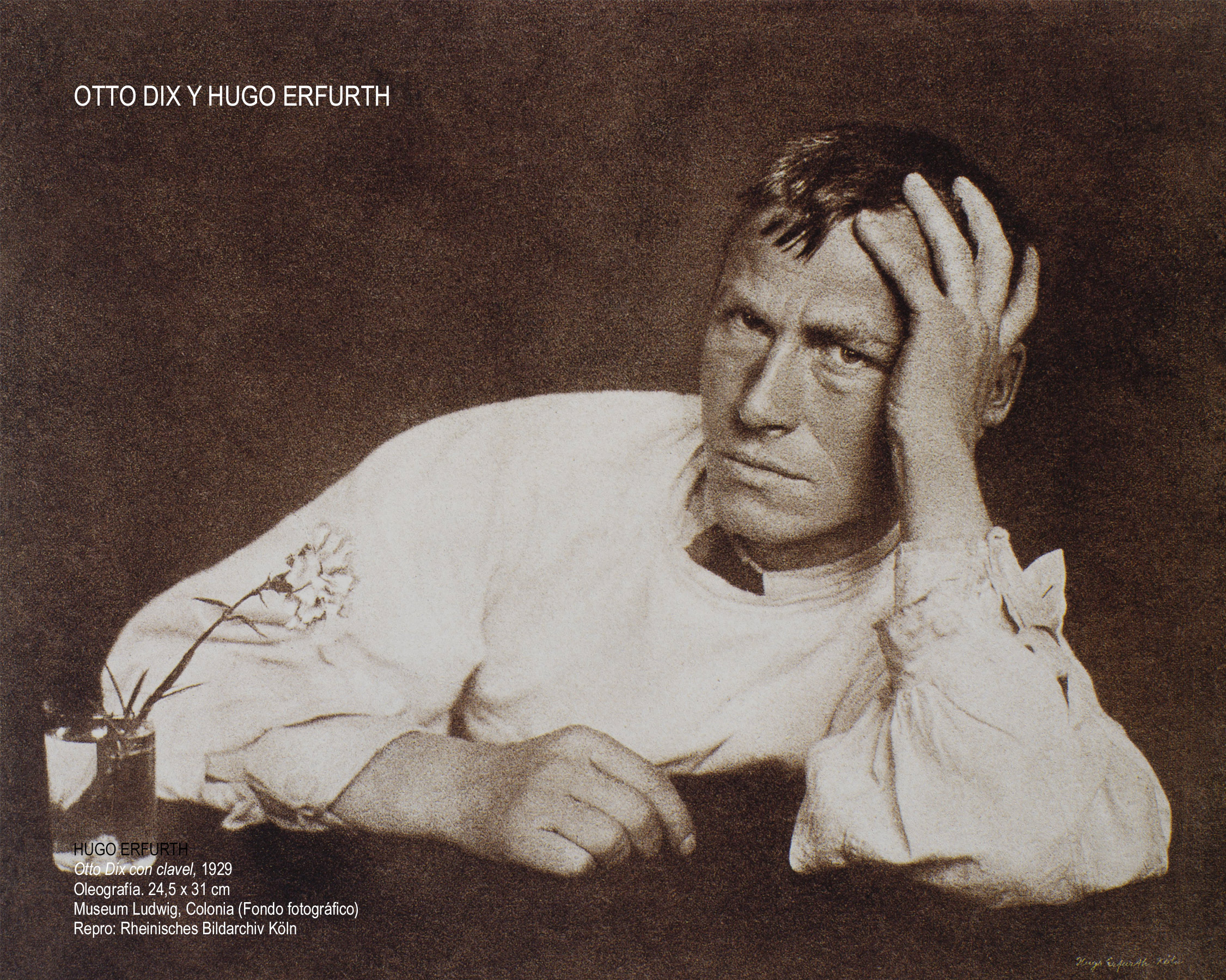

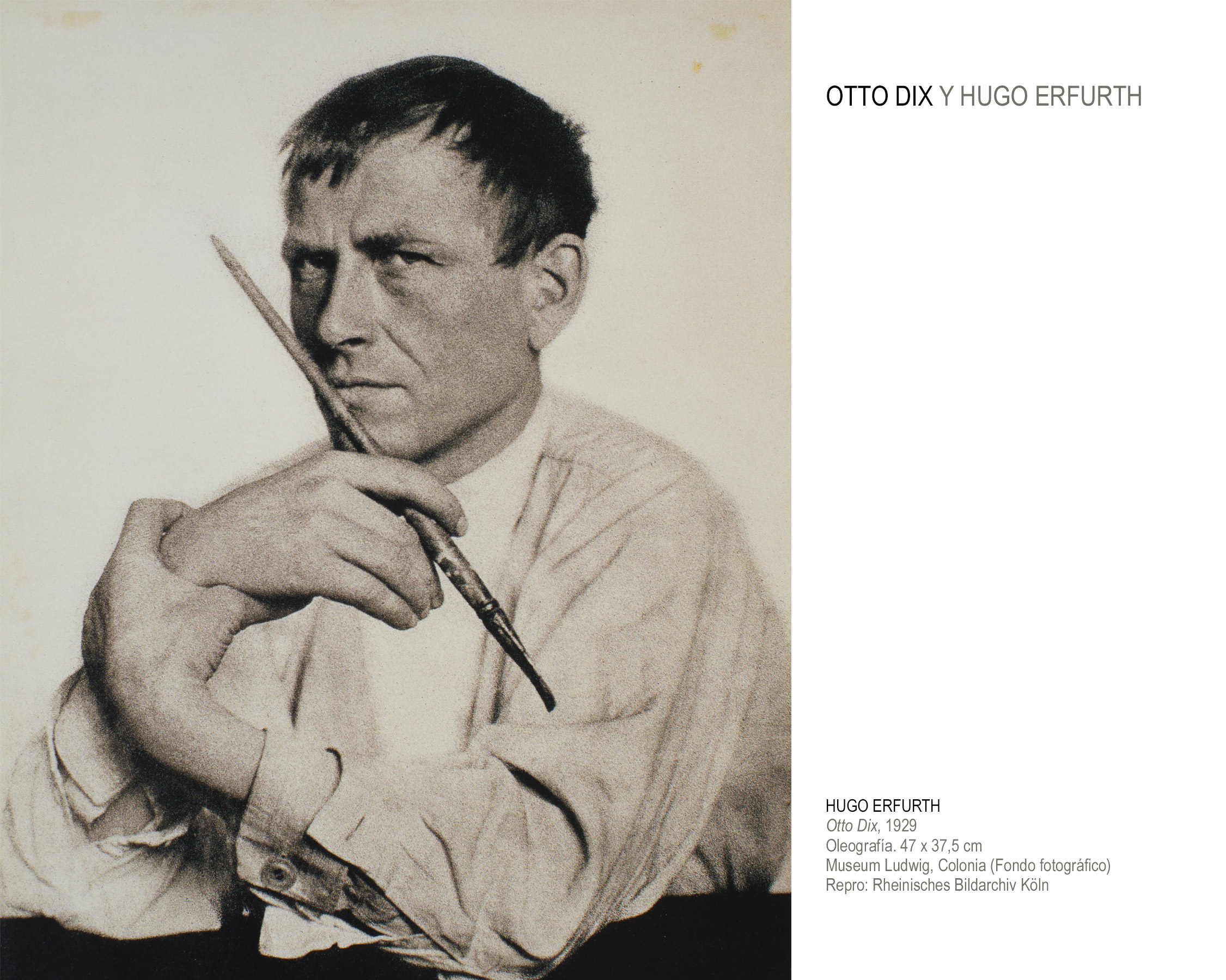

A su llegada a Dresde en 1919 Otto Dix entró en contacto con numerosas personalidades del mundo de la cultura de la ciudad. Hugo Erfurth fue uno de ellos. Quince años mayor que Dix, Erfurth era por aquel entonces un consagrado fotógrafo, por cuyo taller pasarían las principales personalidades de la Alemania de la República de Weimar. Su interés por completar su “galería de cabezas de mi tiempo” hizo que se interesase por fotografiar a la nueva generación de artistas afincados en Dresde, entre los que, desde 1920, se encontraba Dix. Algo más tarde sería Dix, al que también interesaba el género del retrato de una manera especial, el que retrataría en diversas ocasiones a Erfurth (1922, 1925 y 1926).

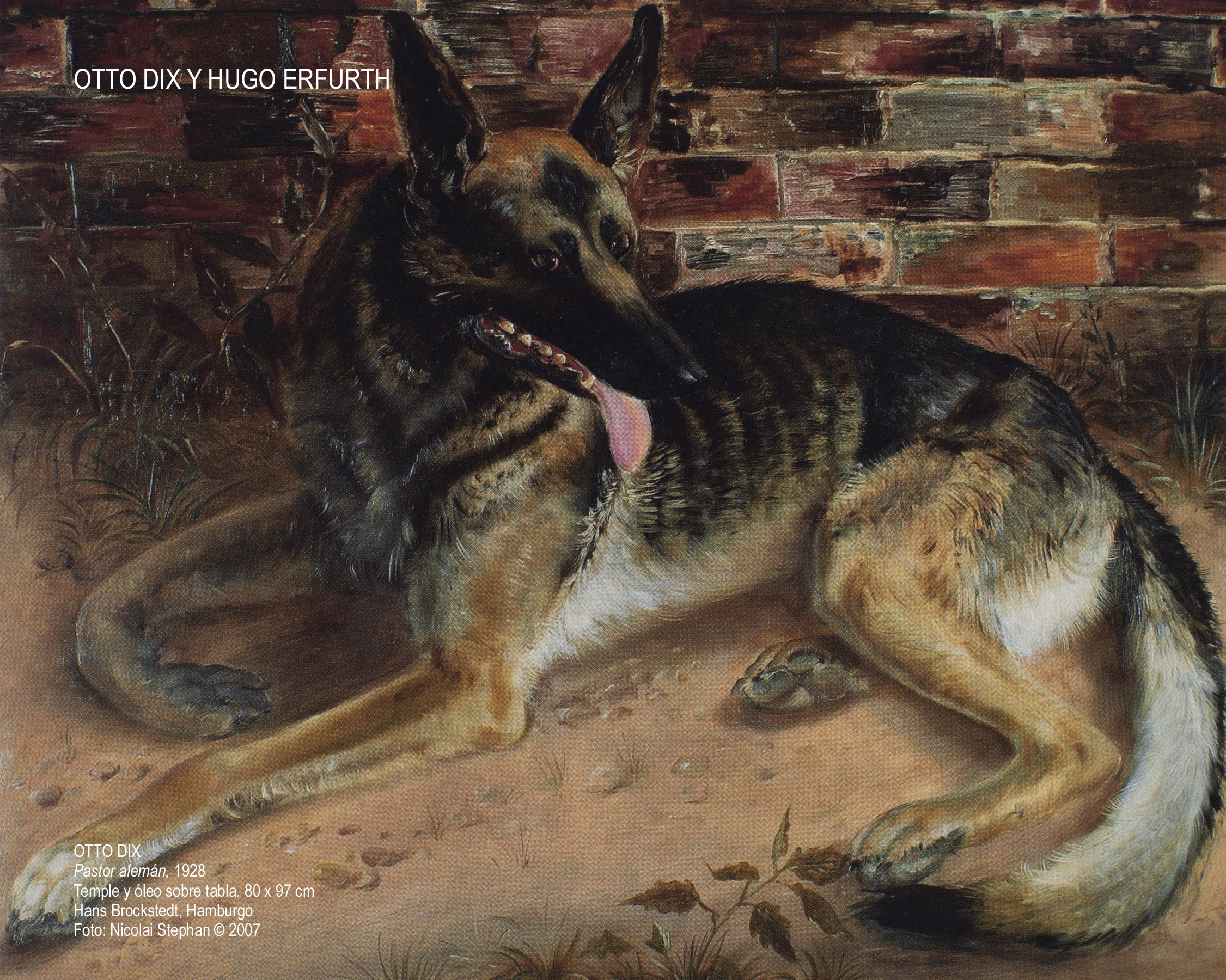

Dix y Erfurth establecieron una estrecha relación de intercambio: Dix realizó varios retratos de Erfurth, su mujer e incluso su perro. A su vez Erfurth inmortalizó a Dix en múltiples ocasiones, con diversos atuendos, junto a su mujer Martha, a sus hijos y a sus padres. Por otro lado Erfurth, dueño de una galería de arte en Dresde, tuvo gran interés en obtener obra sobre papel de Dix y este, a su vez, se sirvió de las fotos de Erfurth de la Primera Guerra Mundial para realizar su serie de aguafuertes sobre la guerra.

En las cerca de veinte obras que se muestran en la exposición se evidencian las mutuas influencias que se establecieron entre Dix y Erfurth a través de sus frecuentes contactos y nos acerca a un capítulo fundamental del debate artístico de los años centrales de la República de Weimar: el parangón entre pintura y fotografía. ¿En qué medida el estilo realista de Dix pudo influir en los retratos fríos y objetivos de Erfurth? Y, por el contrario, ¿hasta qué punto Dix adoptó ciertas notas propias de los retratos de Erfurth?

On his arrival in Dresden in 1919, Otto Dix made contact with numerous figures in the city’s cultural circles. Hugo Erfurth was one such figure. Fifteen years old than Dix, Erfurth was by that time an established photographer and his studio welcomed the leading personalities of the German Weimar Republic. Erfurth’s interest in assembling a “gallery of heads of my time” meant that he was also keen to photograph the new generation of artists living in Dresden, who from 1920 included Dix. Slightly later it would be Dix, who also had a distinctive approach to portraiture, who portrayed Erfurth on a number of occasions (1922, 1925 and 1926).

Dix and Erfurth established a close relationship based on artistic interchange, and Dix executed various portraits of Erfurth, his wife and even his dog. In turn, Erfurth immortalised Dix on numerous occasions and in different dress, together with his wife Martha, their children and parents. In addition, Erfurth, who owned a gallery in Dresden, was extremely interested in acquiring works on paper by Dix, while the painter in turn used Erfurth’s photographs of World War I as the basis for his series of etchings on the war.

The 20 works included in the exhibition reveal the mutual influences that grew up between Dix and Erfurth as a consequence of their regular contacts. They introduce us to a key artistic debate of the middle years of the Weimar Republic concerning the respective merits of painting and photography and which was the superior art form. The exhibition analyses to what degree Dix’s realist style may have influenced Erfurth’s cool, objective portraits, and in contrast, to what extent Dix adopted certain elements characteristic of Erfurth’s photographic portraits.