MUSEO THYSSEN - BORNEMISZA

MUSEO THYSSEN BORNEMISZA

OTTO DIX

TÉCNICAS Y SECRETOS - RETRATO DE HUGO ERFURT

TECHNIQUES AND SECRETS - PORTRAIT OF HUGO ERFURT

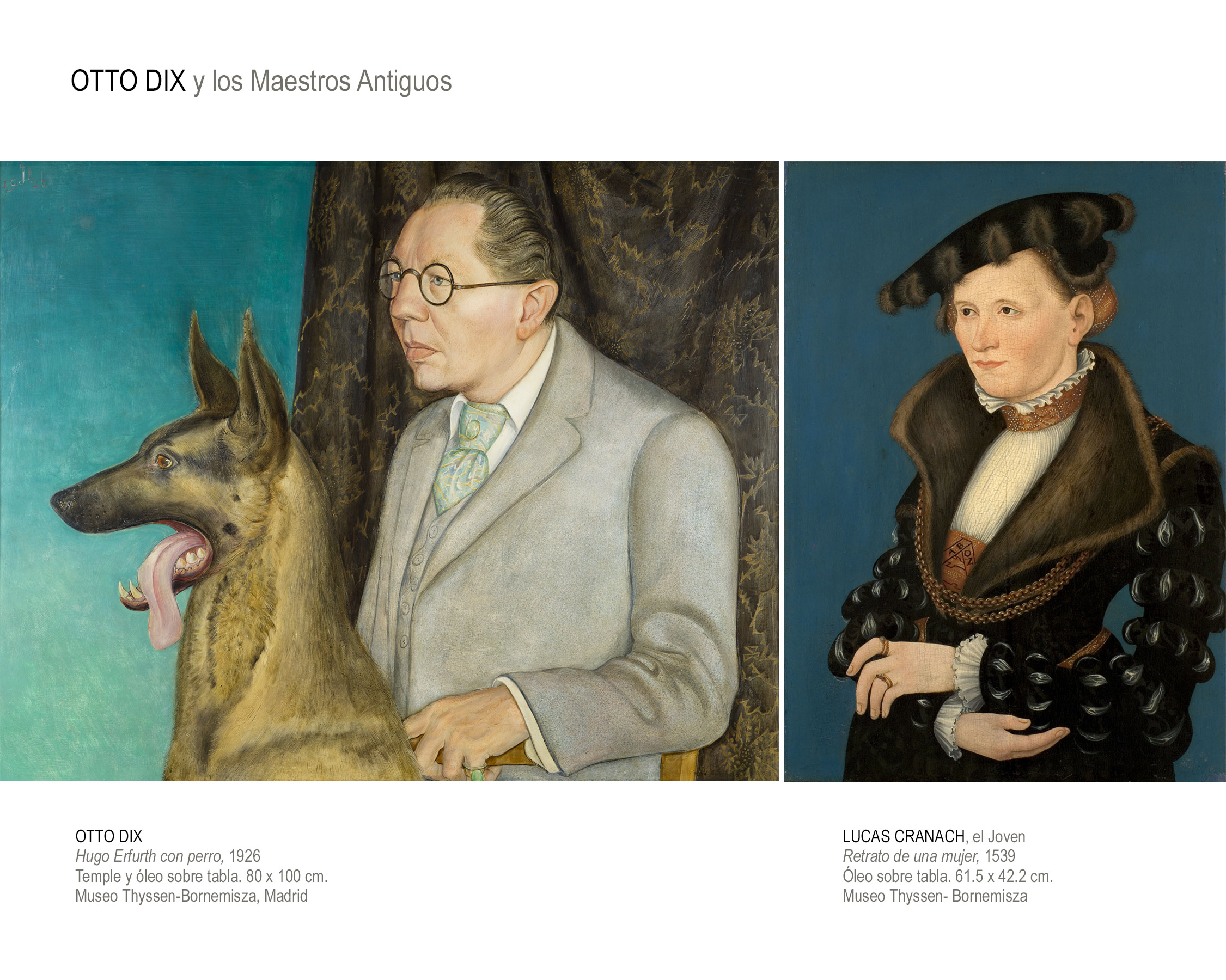

OTTO DIX

Y los Maestros Antiguos

And the Old Masters

Otto Dix, era todavía un pintor joven y desconocido cuando, tras cuatro años en el frente, volvió en 1919 a Dresde. Se inscribió en la Academia de Bellas Artes y - tras algunos experimentos expresionistas, futuristas y dadaístas - finalmente se decantó por un lenguaje realista propio que le permitía mostrar de manera crítica su repulsa por la sociedad que le rodeaba y que le convirtió en uno de los máximos representantes de la Nueva Objetividad (Neue Sachlichkeit). Este estilo verista, con el que captaba los más mínimos detalles con una exactitud enfermiza, estaba en el caso de Dix indisolublemente asociado a un método de trabajo cargado de referencias a la pintura de los grandes maestros del Renacimiento.

“Mi ideal era pintar igual que los maestros del Renacimiento primitivo” afirmaba Otto Dix en 1961. Y ciertamente encontramos huellas de esta pasión por el arte renacentista, tanto italiano como alemán, desde su época de estudiante de la Escuela de Artes y Oficios cuando acudía en sus ratos libres a las magníficas colecciones de arte de Dresde. Sin embargo, fue a mediados de la década de 1920 cuando su empeño por conocer en profundidad y aplicar en sus obras las técnicas de los grandes maestros del Renacimiento se convirtió en una obsesión para él. En sus pinturas no sólo se evidencian ciertas analogías estilísticas o modelos iconográficos y compositivos similares, sino también los mismos procedimientos técnicos. Los dibujos preparatorios y los cartones, la manera de preparar la tabla o la recuperación de la antigua técnica mixta de los maestros alemanes son los elementos que permiten a Dix alcanzar una máxima objetivación y desnudar al retratado más allá de las apariencias.

Para el año 1926, fecha en que Erfurth le encargó su retrato con perro, Dix ya se había convertido en un auténtico maestro antiguo de la modernidad, que dominaba a la perfección los procedimientos de sus antepasados.

Otto Dix was still a young and unknown painter when he returned to Dresden in 1919 after three years at the Front. He enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts where, following various experiments with Expressionism, Futurism and Dada, he finally opted for a distinctive realist idiom that allowed him to offer a critical vision of the society that surrounded him. This new style made Dix one of the leading representatives of the New Objectivity movement (Neue Sachlichkeit). In Dix’s case, his realistic style, which he used to capture the most minute details with an almost unhealthy precision, was associated with a working method that involved numerous references to the art of the great Renaissance masters.

“My ideal was to paint like the Early Renaissance masters”, Dix stated in 1961, and we undoubtedly find evidence of this passion for Renaissance art – both Italian and German – during his time as a student at the School of Arts and Crafts when Dix would spend his free time visiting Dresden’s magnificent art collections. It was, however, from the mid-1920s that his interest in learning and applying the techniques of the great Renaissance artists became a true obsession. Dix’s paintings reveal not only stylistic analogies and similar iconographic and compositional models, but also a use of the same technical procedures. His preparatory drawings and cartoons, his way of preparing the panel and the revival of the old “mixed” technique of the German masters are the elements that allowed the artist to reach the highest level of objectivity and to expose his sitters beyond mere external appearance.

By 1926, the year in which Erfurth commissioned his portrait with his dog, Dix had become a true Old Master of modern art with a perfect command of the techniques of his artistic ancestors.